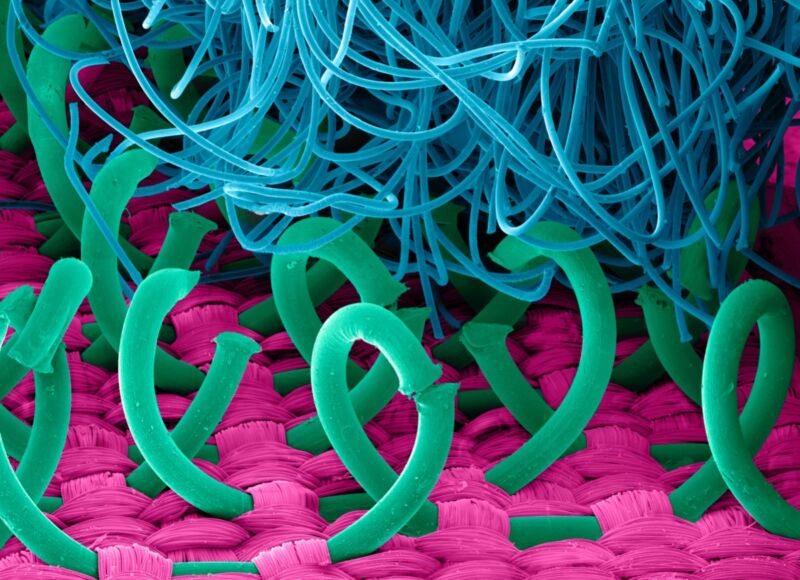

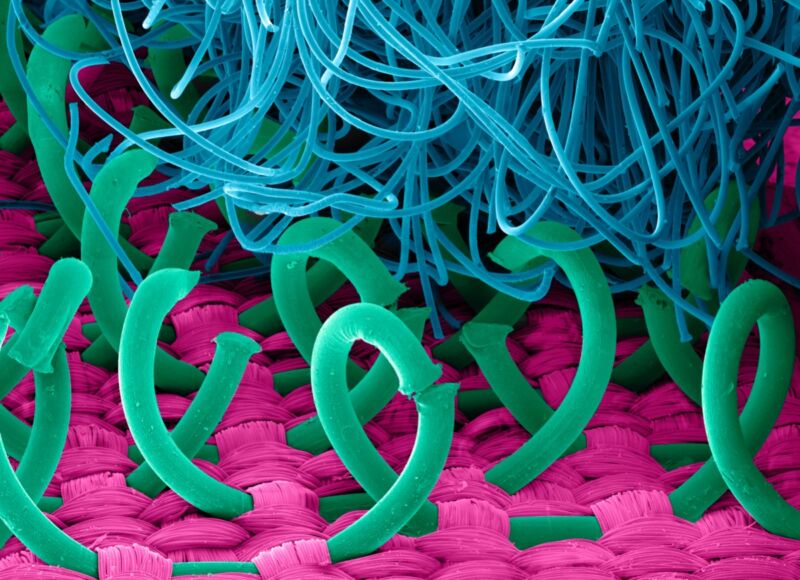

Enlarge / Capturing carbon, as this algae-growing plant does, may not be the most economical way to reach our climate targets. (credit: Santiago Urquijo / Getty Images)

What will it cost if the climate exceeds the Paris Agreement temperature goals this century—even if we later remove carbon dioxide from the air and manage to bring temperatures back down to meet those targets by 2100? And how does that compare with the costs of staying below those targets?

Most plans that are consistent with the Paris Agreement goals assume that temperatures will rise above 1.5° or even 2° C before 2100. They then heavily rely on the success and wide adoption of what are called negative carbon emissions techniques, which involve the removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to bring temperatures back down. That’s a gamble for a number of reasons.

“Betting on being able to bring temperatures down after a larger overshoot is very risky because of the uncertain technological feasibility and because of the possibility of setting off irreversible processes in the earth system with even a temporary temperature overshoot,” wrote second author Christoph Bertram, of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, in an email to Ars Technica. “Furthermore, such an approach would be unfair to future generations, as it basically would shift more of the mitigation burden on them.”